How to cope with acute stress disorder?

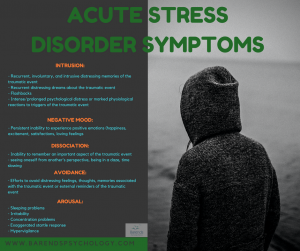

The first symptoms of acute stress disorder (ASD) can appear within a few days after experiencing a traumatic event and have a disruptive effect on daily activities. Concentration problems, the inability to experience positive emotions, recurrent distressing dreams about the event, and irritability are common symptoms of ASD. Coping with acute stress disorder is important in the short run (because it reduces the ASD symptoms [1],[2],[3],[4] and improves the quality of life [5]) and in the long run (because it helps prevent PTSD from developing [1],[2]). Fortunately, coping with acute stress disorder can be done at home and without professional help as long as the ASD symptoms are not too severe. If you are interested in the severity of your symptoms, please take the ASD test.

Go to:

- What is acute stress disorder?

- What causes ASD?

- Diagnosing ASD.

- ASD treatment.

- Helping your partner with ASD.

- Take the ASD test.

- ASD facts.

- Online counseling for ASD.

- Take me to the homepage.

At Barends Psychology Practice acute stress disorder treatment is offered (also online). Go to contact us to schedule a first, free of charge, first session. (Depending on your health insurance, treatment may be reimbursed).

Coping with acute stress disorder – understanding why people suffer from ASD symptoms.

A traumatic event is characterized by the exposure to a life threatening situation, serious injury or sexual violence. Such an experience is extremely upsetting and damages the brain. A growing body of evidence suggests that the brain is significantly affected after someone experiences a traumatic event and develops PTSD or shows signs of PTSD:

- Women who developed PTSD after childhood sexual abuse, compared to those who did not develop PTSD had a smaller volume of the hippocampus [7] of 16%, and 19% smaller compared to women without a history of sexual abuse and PTSD), and women with PTSD showed a failure of left hippocampal activation during a verbal memory task [6].

- Enhanced right amygdala responses (in other words: functional abnormalities in brain responses to emotional stimuli) to ‘masked’ fearful faces are associated with chronic PTSD (already 1 month posttrauma) [8]. By masked, researched meant the following: in a trial people were presented with a picture of a face for 16ms followed by another picture of a face for 100ms. In half of the cases the first image contained a face with an emotoinal expression and the second picture contained a neutral face. In the other half neutral faces were shown for 16ms followed by faces with an emotional expression. Showing a picture for only 16ms is too short to reach the participants’ consciousness, which enables the researcher to measure the pure emotional response.

- Adults with closer proximity to the 9/11 attacks (compared to those who were further away) had lower gray matter volume in amygdala, hippocampus, insula, anterior cingulate, and medial prefrontal cortex (also after controlled for age, gender, and total gray matter volume) [9].

- Lower gray matter volume in left dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) was also found in people who recently experienced a traumatic event and developed PTSD [10], while non PTSD subjects had smaller gray matter volume in the right pulvinar and left pallidum (which is associated with a response to severe stress).

Damage to the brain could explain certain ASD symptoms, such as concentration problems, nightmares, irritability, negative mood, and intense/prolonged psychological distress. Efforts to avoid distressing feelings, thoughts, and memories associated with the traumatic event could be explained as a protection mechanism of the brain to prevent more damage. Unfortunately, avoidant coping is associated with greater PTSD symptoms (and thus ASD symptoms) [11],[12],[17] compared to active coping [12]. Active coping includes strategies such as problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, emotional expression and eliciting social support.

In other words: developing ASD symptoms after experiencing a traumatic event are more common than one may think, and could partially be explained by brain damage. Fortunately, research shows that effective coping with acute stress disorder can reduce the severity of the ASD symptoms.

Coping with acute stress disorder – reducing ASD symptoms.

There are a few things you can do to reduce the impact ASD symptoms have on you. Some of these things may feel counterintuitive, others may take a while before you notice a difference, but their effectiveness is supported by literature. People who start coping with acute stress disorder soon after the traumatic event experience control and power over their symptoms and themselves, whereas feelings of helplessness are being reduced [13].

- Cognitive appraisal: The way someone perceives a stressor determines the psychobiological reaction one has. If someone perceives a stressor as a threatening (possibility of danger/harm), the person will experience more negative emotions, more stress, and feelings of hopelessness. If, however, someone perceives a stressor as challenging (opportunity for gain), the person experiences low negative emotions, positive arousal, and feelings of being in control [13],[16]. In other words, it is important to look at certain tasks as challenges that you can do, instead of seeing them as threatening or too difficult. For instance, experiencing sudden feelings of panic or anxiety. These feelings are common after a traumatic event. Instead of perceiving them as a threat, realize that these feelings are temporary and will disappear soon. Often, these are caused by scary thoughts. These thoughts are often irrational and not true. Thoughts, just like feelings, are temporary and cannot really hurt you. Cognitive appraisal is one of the most effective strategies when it comes to coping with acute stress disorder.

- Social support: People who use their social network to talk about the traumatic event, report less ASD & PTSD symptoms, compared to those who socially withdraw [14],[16]. Also, people who use their social network were less likely to develop ASD and PTSD [15]. Having unwanted thoughts, feelings, and memories is normal after a traumatic event. Instead of avoiding these thoughts, try to talk about them with someone. This way you are processing your thoughts, feelings, and memories. Not processing them is associated with PTSD symptoms.

- Distraction: People who distract themselves (keeping themselves occupied) are less likely to develop ASD and PTSD, compared to those who do not keep themselves occupied [15]. Try to find positive ways to distract yourself, and express your feelings in a creative way. Having flashbacks is common for those who experienced a traumatic event. Distracting yourself will stop the flashback. Simple activities, like walking around, talking to someone or doing a sudoku/puzzle are very effective. Make sure that these activities can’t be done on automatic pilot, because that way your flashback will continue.

- Religious coping: People who use religious or spiritual coping strategies are more likely to recover from ASD and PTSD symptoms, compared to people who do not use these coping strategies. Interestingly, people who use religious coping strategies recover faster/more than those who use spiritual coping strategies [16]. Using religion or spirituality as a strategy for coping with acute stress disorder reduces PTSD and ASD symptoms.

- Rhythm: Keeping a regular bedtime schedule will reduce the chance that you experience sleeping problems, concentration problems, anger and irritability. In general, keeping a healthy rhythm, makes it easier for your body and mind to prepare for what is coming and that helps people to reduce experiencing negative feelings and emotions. Other ways to cope with anger and irritability: distract yourself (drink a glass of water) when you are upset, remember that these feelings are common right after a traumatic event, inform the people around you about your recent experience and let them know that your emotional response may be out of character for a while. This will change their approach towards you and reduces the chance that they will push the wrong buttons.

- Talk to a therapist: If you have the feeling that coping with acute stress disorder is too difficult to do all by yourself, please reach out to a therapist. At Barends Psychology Practice, the first session is free of charge, and without obligation. We can talk about your traumatic event and the symptoms you are suffering from. Together we can set up a treatment plan and help you to recover.

Literature

- [1] Kornør, H., Winje, D., Ekeberg, Ø., Weisæth, L., Kirkehei, I., Johansen, K., & Steiro, A. (2008). Early trauma-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy to prevent chronic post-traumatic stress disorder and related symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry, 8, 81.

- [2] Ponniah, K., & Hollon, S. D. (2009). Empirically supported psychological treatments for adult acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a review. Depression and anxiety, 26, 1086-1109.

- [3] Forbes, D., Creamer, M., Phelps, A., Bryant, R., McFarlane, A., Devilly, G. J., … & Newton, S. (2007). Australian guidelines for the treatment of adults with acute stress disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 41, 637-648.

- [4] Holbrook, T. L., Hoyt, D. B., Coimbra, R., Potenza, B., Sise, M., & Anderson, J. P. (2005). High rates of acute stress disorder impact quality-of-life outcomes in injured adolescents: mechanism and gender predict acute stress disorder risk. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 59, 1126-1130.

- [5] Van Emmerik, A. A., Kamphuis, J. H., & Emmelkamp, P. M. (2008). Treating acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with cognitive behavioral therapy or structured writing therapy: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 77, 93-100.

- [6] Bremner, J. D., Vythilingam, M., Vermetten, E., Southwick, S. M., McGlashan, T., Nazeer, A., … & Ng, C. K. (2003). MRI and PET study of deficits in hippocampal structure and function in women with childhood sexual abuse and posttraumatic stress disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 924-932.

- [7] Villarreal, G., Hamilton, D. A., Petropoulos, H., Driscoll, I., Rowland, L. M., Griego, J. A., … & Brooks, W. M. (2002). Reduced hippocampal volume and total white matter volume in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological psychiatry, 52, 119-125.

- [8] Armony, J. L., Corbo, V., Clément, M. H., & Brunet, A. (2005). Amygdala response in patients with acute PTSD to masked and unmasked emotional facial expressions. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1961-1963.

- [9] Ganzel, B. L., Kim, P., Glover, G. H., & Temple, E. (2008). Resilience after 9/11: multimodal neuroimaging evidence for stress-related change in the healthy adult brain. Neuroimage, 40, 788-795.

- [10] Chen, Y., Fu, K., Feng, C., Tang, L., Zhang, J., Huan, Y., … & Ma, C. (2012). Different regional gray matter loss in recent onset PTSD and non PTSD after a single prolonged trauma exposure. PLoS One, 7, e48298.

- [11] Lawrence, J. W., & Fauerbach, J. A. (2003). Personality, coping, chronic stress, social support and PTSD symptoms among adult burn survivors: a path analysis. The Journal of burn care & rehabilitation, 24, 63-72.

- [12] Iverson, K. M., Litwack, S. D., Pineles, S. L., Suvak, M. K., Vaughn, R. A., & Resick, P. A. (2013). Predictors of intimate partner violence revictimization: The relative impact of distinct PTSD symptoms, dissociation, and coping strategies. Journal of traumatic stress, 26, 102-110.

- [13] Olff, M., Langeland, W., & Gersons, B. P. (2005). The psychobiology of PTSD: coping with trauma. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 30, 974-982.

- [14] Pietrzak, R. H., Harpaz-Rotem, I., & Southwick, S. M. (2011). Cognitive-behavioral coping strategies associated with combat-related PTSD in treatment-seeking OEF–OIF veterans. Psychiatry Research, 189, 251-258.

- [15] Holeva, V., Tarrier, N., & Wells, A. (2001). Prevalence and predictors of acute stress disorder and PTSD following road traffic accidents: Thought control strategies and social support. Behavior Therapy, 32, 65-83.

- [16] Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of loss and trauma, 14, 364-388.

- [17] Pineles, S. L., Mostoufi, S. M., Ready, C. B., Street, A. E., Griffin, M. G., & Resick, P. A. (2011). Trauma reactivity, avoidant coping, and PTSD symptoms: A moderating relationship?. Journal of abnormal psychology, 120, 240.