Understanding Burnout

Burnout was first used in the 1970s to describe the stress-related consequences faced by healthcare workers. Today, burnout can affect anyone—from teachers and bankers to self-employed individuals and managers [1],[2],[3],[4].

Symptoms of burnout develop when someone experiences prolonged stress without enough emotional and physical recovery. Common symptoms include:

• Exhaustion

• Cognitive problems (e.g., difficulty concentrating)

• Reduced empathy, motivation, and creativity

• Cynicism and irritability

• Increased sick leave

Burnout can worsen after traumatic or highly stressful events, as it becomes harder to focus on personal needs. Neglecting self-care, such as healthy eating, rest, exercise, and social interaction, can lead to additional issues like sexual dysfunction, appetite loss, and angry outbursts [3],[6],[7].

Go to:

At Barends Psychology Practice, we offer effective treatment for burnout. Contact us to schedule a first, free session.

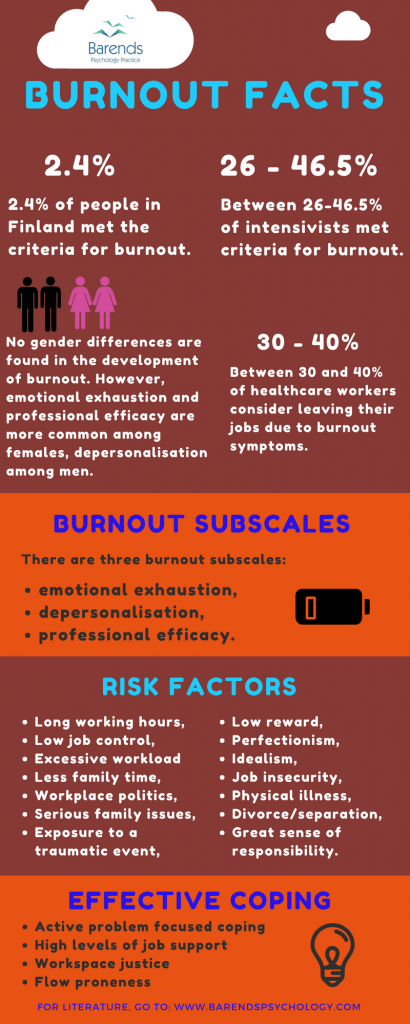

Burnout Subscales

Burnout symptoms are grouped into three subscales [5]:

1. Emotional Exhaustion: Feeling drained, lacking energy, and unable to recharge.

2. Depersonalization: A distorted view of oneself and others, marked by a lack of empathy, isolation, and loss of motivation.

3. Professional Efficacy: Difficulty focusing, listlessness, and a negative attitude toward tasks.

Research [8] shows that women tend to score higher in emotional exhaustion and professional efficacy, while men score higher in depersonalization. Depersonalization may temporarily reduce stress, but professional inefficacy increases it, particularly in high-stress fields like academia.

(Advertisement. For more information, please continue reading.)

On average, women score higher on the subscales emotional exhaustion and professional efficacy, whereas men score higher on depersonalisation [11]. Depersonalisation reduces stress, whereas professional efficacy increases stress [12]. The latter can be seen in academia where a lot of people with a PhD experience burnout symptoms. Read more about it here. In other words: a lack of empathy and reduced motivation and a negative attitude towards tasks seem to reduce stress levels. Unfortunately, these coping mechanisms are not enough to get rid of burnout.

Burnout versus depression

Burnout and depression share symptoms like fatigue, concentration issues, and sleep problems, but there are key differences:

• Depressed individuals often feel inferior or experience a loss of status [17], while burnout tends to be work-related.

• Severe burnout can lead to depression, with 87.5% of burned-out individuals meeting criteria for Major Depressive Disorder.

Individuals who are severely burned out more often meet the criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (87.5%), than vice versa (26.2%), which suggests that burnout may lead to depression [18],[19],[20],[21]. Also, depression is associated with a lack of reciprocity in private life, whereas burned out individuals experience a lack of reciprocity at work (but not in private life) [20].

Impact of Burnout on Work

Burnout reduces productivity [16], leads to longer sick leave [14],[15], and increases the likelihood of future absences due to mental or physical health issues [13],[14]. Many burned-out employees continue working [15], resulting in lower engagement, more mistakes, and higher costs for employers.

How Business Coaching Can Help Prevent Burnout

Burnout often happens when stress builds up and people don’t have the tools or support to manage it. Business coaching can make a big difference by providing guidance and practical strategies to reduce stress and improve well-being. Here’s how:

1. Better Time Management

Coaching helps you prioritize tasks, delegate responsibilities, and set boundaries, so you can focus on what matters most without feeling overwhelmed.

2. Improved Communication Skills

Learning how to communicate effectively with colleagues and employees can reduce workplace conflict, misunderstandings, and frustration.

3. Clearer Goals and Direction

Coaches help you define achievable goals and create a step-by-step plan, giving you a sense of control and purpose.

4. Building Resilience

Coaching focuses on strengthening your ability to handle challenges, recover from setbacks, and maintain a positive mindset.

5. Work-Life Balance

Coaching encourages healthy habits, such as taking breaks, staying active, and making time for personal interests, which are essential for preventing burnout.

6. Support and Accountability

A coach acts as a sounding board and motivator, ensuring you stay on track and feel supported as you make changes.

With the right coaching, you can reduce stress, boost your energy, and enjoy a more balanced and fulfilling professional life.

Go to:

(Advertisement. For more information, please continue reading.)

Literature

- [1] Embriaco, N., Azoulay, E., Barrau, K., Kentish, N., Pochard, F., Loundou, A., & Papazian, L. (2007). High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 175, 686-692.

- [2] Vercambre, M. N., Brosselin, P., Gilbert, F., Nerrière, E., & Kovess-Masféty, V. (2009). Individual and contextual covariates of burnout: a cross-sectional nationwide study of French teachers. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 333.

- [3] Khattak, J. K., Khan, M. A., Haq, A. U., Arif, M., & Minhas, A. A. (2011). Occupational stress and burnout in Pakistans banking sector. African Journal of Business Management, 5, 810-817.

- [4] Jamal, M. (2007). Burn-out and self‐employment: a cross‐cultural empirical study. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 23, 249-256.

- [5] INTeReSTS, D. O. (2015). Burnout in physicians. JR Coll Physicians Edinb, 45, 104-7.

- [6] Leiter, M. P. (2005). Perception of risk: An organizational model of occupational risk, burn-out, and physical symptoms. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 18, 131-144.

- [7] Schaufeli, W. B., & Maslach, C. (2017). Historical and conceptual development of burn-out. In Professional burnout (pp. 1-16). Routledge.

- [8] Gorter, R., Freeman, R., Hammen, S., Murtomaa, H., Blinkhorn, A., & Humphris G. (2008). Psychological stress and health in undergraduate dental students: fifth year outcomes compared with first year baseline results from five European dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ., 12, 61–68.

- [9] Michal, M., Sann, U., Niebecker, M., Lazanowsky, C., Kernhof, K., Aurich, S., … & Berrios, G. E. (2004). Die Erfassung des Depersonalisations-Derealisations-Syndroms mit der Deutschen Version der Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale (CDS). PPmP-Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie, 54, 367-374.

- [10] Eckhardt-Henn, A. (2004). Dissoziative Störungen des Bewusstseins. Psychotherapeut, 49, 55-66.

- [11] Vercambre, M. N., Brosselin, P., Gilbert, F., Nerrière, E., & Kovess-Masféty, V. (2009). Individual and contextual covariates of burnout: a cross-sectional nationwide study of French teachers. BMC Public Health, 9, 333.

- [12] McManus, I. C., Winder, B. C., & Gordon, D. (2002). The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. The Lancet, 359, 2089-2090.

- [13] Toppinen-Tanner, S., Ojajärvi, A., Väänaänen, A., Kalimo, R., & Jäppinen, P. (2005). Burnout as a predictor of medically certified sick-leave absences and their diagnosed causes. Behavioral medicine, 31, 18-32.

- [14] Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Van Rhenen, W. (2009). How changes in job demands and resources predict burnout, work engagement, and sickness absenteeism. Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 30, 893-917.

- [15] Peterson, U., Demerouti, E., Bergström, G., Åsberg, M., & Nygren, Å. (2008). Work characteristics and sickness absence in burnout and nonburnout groups: A study of Swedish health care workers. International Journal of stress management, 15, 153.

- [16] Nayeri, N. D., Negarandeh, R., Vaismoradi, M., Ahmadi, F., & Faghihzadeh, S. (2009). Burnout and productivity among Iranian nurses. Nursing & health sciences, 11, 263-270.

- [17] Brenninkmeyer, V., Van Yperen, N. W., & Buunk, B. P. (2001). Burnout and depression are not identical twins: is decline of superiority a distinguishing feature?. Personality and individual differences, 30, 873-880.

- [18] Ahola, K., Honkonen, T., Isometsä, E., Kalimo, R., Nykyri, E., Aromaa, A., & Lönnqvist, J. (2005). The relationship between job-related burn-out and depressive disorders—results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Journal of affective disorders, 88, 55-62.

- [19] Hakanen, J. J., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2012). Do burn-out and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. Journal of affective disorders, 141, 415-424.

- [20] Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Demerouti, E., Janssen, P. P., Van Der Hulst, R., & Brouwer, J. (2000). Using equity theory to examine the difference between burn-out and depression.

- [21] Wurm, W., Vogel, K., Holl, A., Ebner, C., Bayer, D., Mörkl, S., … & Hofmann, P. (2016). Depression-burn-out overlap in physicians. PloS one, 11.