What are specific phobias?

Specific phobias involve persistent and irrational fears of a specific situation or object that is out of proportion to the actual risk. This strong fear makes a person want to avoid the objects, animals or situations that provoke responses typical for specific phobias: panic, anxiety, racing heart, and a strong desire to leave the situation early. People suffering from specific phobias not only avoid the feared objects or animals itself, but often also videos or images of the phobic object, animal or situation. Thinking of the feared animal or object can already make people feel sick, nausea, and scared. In other words: if someone suffers from Arachnophobia (fear of spiders) then that person will avoid direct contact and will try to leave the situation as soon as possible (safety behaviour). In severe cases, even a picture of a spider or talking about a spider (movie) can trigger signs of fear and discomfort. Here are a few examples of common specific phobias: fear of dogs, fear of heights, fear of spiders, fear of snakes, fear of blood, fear of flying.

Go to:

- Specific phobia symptoms.

- Specific phobia causes.

- Specific phobia treatment.

- Coping with phobias.

- Partner with specific phobia.

At Barends Psychology Practice, we offer (online) counseling for specific phobias. Contact us to schedule a first, free of charge, online session. (Depending on your health insurance, treatment may be reimbursed).

Specific phobias – different kinds

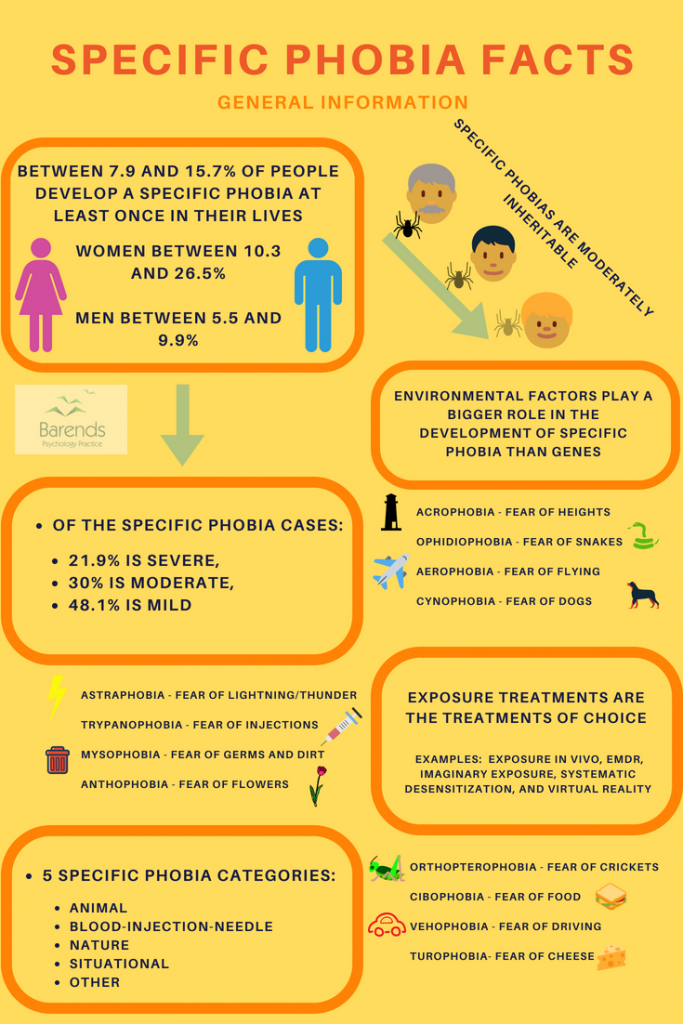

For every situation, animal (including humans) or object someone can develop a specific phobia. Developing specific phobias is very personal and many people assume they seem to be unrelated to anything. However, the development of phobias can be traced back to classical conditioning, modelling, and/or negative information transmission [11], and explains why the age of onset for specific phobias is between 6 and 11 years [11]; children use these strategies a lot to learn and develop. Interestingly, the age of onset is not the same for every specific phobia, just like its prevalence. Researchers found that there are 5 different subtypes of specific phobias:

- (1) Situations – fear of air planes or enclosed places, (in 1.9% of people; age: 15.5)

- (2) Nature – fear of heights or thunder, (in 2.6% of people; age: 3)

- (3) Animals or insects – fear of spiders or horses, (in 5.0% of people; age 4)

- (4) Blood, injection or injury – fear of needles or blood, (in 2.4% of people; age: 6)

- (5) Other phobias – fear of clowns or men or blushing, (in 0.6% of people; age: 5)

We are interested in which specific phobia subtype you are suffering from:

For interesting facts about these specific phobias go to: interesting specific phobia facts.

Specific phobias – safety behaviours.

One of the most common phobias are Arachnophobia (fear of spiders), social phobia (fear of social situations), and Agoraphobia (fear of crowds and fear of open spaces). Between 17 and 55% of people suffer from Arachnophobia [1],[2], between 9 and 21% of people suffer from social phobia [3],[4],[5],[6], and between 1.27 and 9.8% of people suffer from Agoraphobia [6],[7],[8].

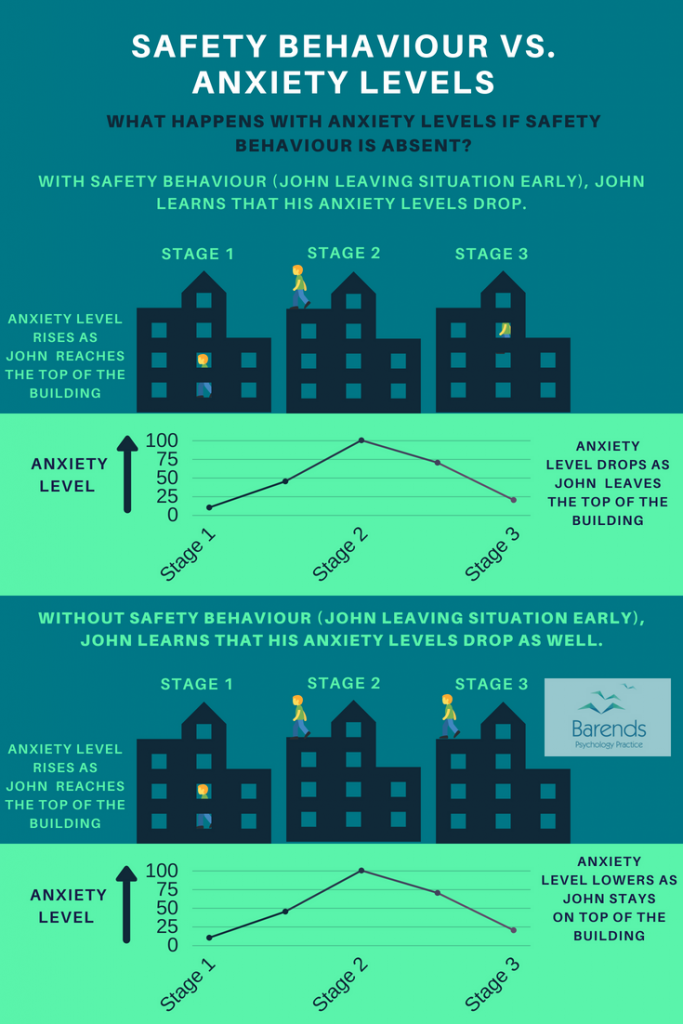

Dealing with specific phobias can be done in a variety of ways. Someone with Arachnophobia can avoid spiders as much as possible and accept certain limitations in their life, such as camping and gardening. Usually, people develop one or two safety behaviours to help them cope with the phobic situation, animal or object, as can be seen in the image on the right (or above). Safety behaviours or objects are rituals, compulsions, objects or people that help reduce anxiety levels in people with specific phobias or other mental disorders.

(Advertisement. For more information, continue reading.)

Relationship safety behaviour and anxiety levels

Person with acrophobia.

Person with acrophobia.

Although safety behaviours are effective in the short run (they help someone with specific phobia to cope with the situation), they are ineffective in the long run. By using safety behaviour a person learns that anxiety levels only reduce when applying that behaviour or using that object. It is true that anxiety levels reduce when facing the phobic situation, animal or object, but it’s not due to safety behaviour; in fact it is despite safety behaviour. After exposing oneself for 10 to 30 minutes to the phobic animal, situation or object, anxiety levels reduce if the person stays near the phobic animal, situation or object [9],[10].

In the image above or on the right, a person with acrophobia (fear of heights) takes the elevator to the top floor to observe his anxiety levels. As expected, the closer he gets to the top floor the higher his anxiety levels. When he is on the top of the building he has a racing heart, he starts to tremble, shake, and sweat, and has a feeling he may faint. Yet, after 10 minutes, he notices that his heartbeat slows down, he stops shaking and trembling, and he does not feel faint anymore. Only his hands are still sweaty. He did not apply avoidant safety behaviour, but notices that he calms down by himself. If this person repeats this exercise a couple of times, he will notice that his physical symptoms reduce significantly and that he will not feel as anxious anymore. This strategy could also be used for other phobias.

(Advertisement. For more information, please scroll down.)

Safety behaviour at the start of therapy

Safety behaviour can reduce anxiety levels in the short run and therapy could benefit from it, especially in the early stages [9]. In therapy, safety behaviour is used as a last resort (leave the situation early) or to help the person cope with the situation (taking your partner with you in the elevator, in case you have a fear of elevators – there is no official name for it). In the latter case, the person experiences that taking the elevator will not result in getting stuck or falling down, which is a success experience. Important for the patient and for therapy effectiveness is to slowly reduce the availability of the safety behaviour or object. This way the patient learns that they can do it on their own.

[/responsivevoice]

Literature

-

- [1] Wagener, A. L. (2012). The mechanisms of change associated with exposure in act versus CBT for treatment of arachnophobia (Doctoral dissertation, Wichita State University).

- [2] Naveed, S., Sana, A., Rehman, H., Qamar, F., Abbas, S. S., Khan, T., … & Hameed, A. (2015). Prevalence and Consequences of PHOBIAS, Survey Based Study in Karachi. J Bioequiv Availab, 7, 140-143.

- [3] Ghazwani, J. Y., Khalil, S. N., & Ahmed, R. A. (2016). Social anxiety disorder in Saudi adolescent boys: Prevalence, subtypes, and parenting style as a risk factor. Journal of family & community medicine, 23, 25.

- [4] Burstein, M., He, J. P., Kattan, G., Albano, A. M., Avenevoli, S., & Merikangas, K. R. (2011). Social phobia and subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement: prevalence, correlates, and comorbidity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 50, 870-880.

- [5] GÜLTEKIN, B. K., & Dereboy, I. F. (2011). The prevalence of social phobia, and its impact on quality of life, academic achievement, and identity formation in university students. Turk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 22, 150.

- [6] Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2012). Twelve‐month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 21, 169-184.

- [7] Stein, D. J., Seedat, S., Herman, A., Moomal, H., Heeringa, S. G., Kessler, R. C., & Williams, D. R. (2008). Lifetime prevalence of psychiatric disorders in South Africa. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 112-117.

- [8] Grant, B. F., Hasin, D. S., Stinson, F. S., Dawson, D. A., Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S., … & Saha, T. D. (2006). The epidemiology of DSM-IV panic disorder and agoraphobia in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. The Journal of clinical psychiatry.

- [9] Rachman, S., Radomsky, A. S., & Shafran, R. (2008). Safety behaviour: A reconsideration. Behaviour research and therapy, 46, 163-173.

- [10] Okajima, I., Kanai, Y., Chen, J., & Sakano, Y. (2009). Effects of safety behaviour on the maintenance of anxiety and negative belief social anxiety disorder. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 55, 71-81.

- [11] Merckelbach, H., de Jong, P. J., Muris, P., & van Den Hout, M. A. (1996). The etiology of specific phobias: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 16, 337-361.