What is burnout?

Where burnout used to be a phenomenon in healthcare professionals with stressful jobs, nowadays burnout is common and seen in a variety of professions, such as teachers, managers, bankers, and sole traders [1],[8],[23],[26]. Despite the fact that burnout is more common these days, finding proper burnout facts is still difficult. This page focuses on interesting burnout facts obtained from scientific articles. For instance, on the three burnout subscales researchers have identified, causes and risk factors that contribute to the development of burnout in people, and other noteworthy burnout facts.

In order to provide you with the most up to date burnout facts, this is page is updated on a regular basis. The last update: January 2019.

Go to:

- Helping your burned out partner.

- Take the burnout test.

- Dealing with PhD stress.

- Online counseling.

- Take me to the homepage.

At Barends Psychology Practice, treatment for burnout is offered. Go to contact us to schedule a first, free of charge, session. (Depending on your health insurance, treatment may be reimbursed).

Burnout facts – general

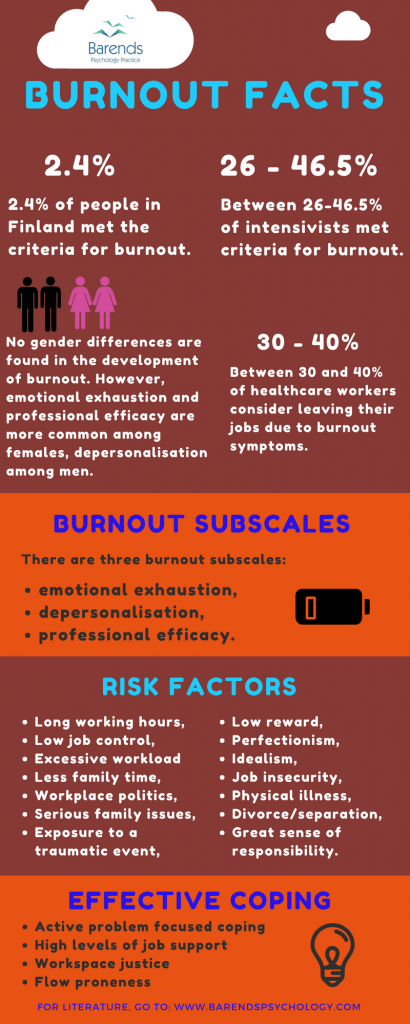

- In Finland, 2.4% of people had severe burnout and 25.2% had mild burnout [7].

- Men and women are equally likely to develop burnout, in Finland [7]. Other studies also found no gender differences in the development of burnout [3].

- There are three burnout subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and professional efficacy [22]. This indicates that not all burnout clients should receive the same kind of treatment.

- People with global burnout or those who scored high on the subscale emotional exhaustion showed the strongest and consistent negative associations to cortisol in the afternoon, evening, and 30 minutes after waking up [17]. Too much cortisol can cause severe mood swings, too little cortisol could cause fatigue.

- Between 30 and 40% of healthcare workers consider leaving their jobs due to burnout symptoms [3],[6].

Burnout facts – risk factors and causes

- 80% of the people with burnout report work-related problems as a reason for their burnout; 39% reported that work was the only reason for their burnout [8],[10].

- Long working hours, low job control, excessive workload (and consequently less family time), workplace politics, job insecurity, low reward, but also perfectionism, idealism and a great sense of responsibility could cause burnout [19],[22],[23].

- People who experienced one or more traumatic events are more likely to have a burnout. The more significant life events one experiences, the higher the chance of developing burnout [15]. Other risk factors are serious family problems, physical illness, divorce or separation [15]. Position in society can also affect if a person is experiencing psychological pressure. Mental burnout often occurs in people who win or lose at gambling. Those who love to play poker, roulette are at particular risk.

- Organizational factors, such as a high workload, conflicts with colleagues or exposure to traumatic events are associated with burnout symptoms [1],[3].

- In Finland, people who have severe burnout are more likely to develop a depressive disorder. 50% of those with severe burnout had some depressive disorder, compared to only 7.3% of people without burnout [7]. Those with current major depressive disorder suffered from severe burnout more often than those who previously had major depressive disorder [7].

- Genetic factors play a role in burnout symptoms; between 30 and 33% of the burnout symptoms can be explained through genetic factors [12],[13]. 67% of the burnout symptoms can be explained through environmental factors [12]. On the subscale emotional exhaustion, 13% of the symptoms could be explained through genetic factors in women, and 30% in men [28][29]. These findings are in line with other studies stressing the impact working environment has on the development of burnout.

Burnout facts – symptoms

- Common burnout symptoms are extreme tiredness, emotional exhaustion, back pain, headache, sleeping problems, gastrointestinal disturbance, inability to concentrate, difficulties in decision making, irritability, sexual problems, lack of appetite, shortness of breath, chronic fatigue, and social withdrawal [23],[24],[25].

- Burned out people make significantly more cognitive mistakes in daily life than people without burnout. Also, burned out people have more difficulty with inhibition and perform worse on attention tasks [18].

- People with burnout score markedly lower in all subscales of health-related quality of life questionnaires, compared to healthy individuals who worked full-time [10].

Burnout fact – professions

- Between 26 and 46.5% of the intensivists and medical graduates reported a high level of burnout [1],[2],[3].

- According to a systematic review of 25 years, gender was not found to be predictive of burnout in emergency nurses [3]. However, female intensivists were 60% more likely to develop burnout than men [1].

- Younger, unmarried, and/or childless emergency nurses and intensivists were more likely to develop burnout [1],[3].

- Female teachers are more likely to score higher on the burnout dimensions: emotional exhaustion and reduced personal accomplishment, whereas male teachers are more likely to score high on the burnout dimension depersonalization [8]. This is in line with findings in healthcare workers.

- In Pakistan, there is a tendency to significant physical burnout among bank employees [23]. Long working hours, insufficient time with family, inadequate salary, job related worries, and negative feelings about work contribute significantly to the experienced stress bank employees reported.

- Self-employed individuals experienced higher overall burnout, emotional exhaustion, and lack of accomplishment, than organizationally employed individuals, in both Pakistan and Canada [26]

- One in every two physicians in Austria is affected by symptoms of burnout. Younger physicians were more often affected by burnout and depression symptoms, than older physicians [27].

- Physicians who are severly burned out more often meet the criteria for Major Depressive Disorder (26.2%), than vice versa (87.5%) [27].

- In China, physicians who worked 60+ hours per week or who reported serious burnout, reported more medical mistakes. 39.6%, 50.0%, and 59.5% of the physicians in primary, secondary, and tertiary hospitals in China respectively reported having made medical mistakes over the course of the previous year [30].

Burnout facts – coping strategies

- Active problem focused coping is associated with lower levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and with higher personal accomplishment [4],[5],[16]. However, passive avoidant and emotional coping strategies were found to be ineffective in dealing with stress [4],[5],[16].

- Flow proneness helps reducing emotional problems at work [13], but more research is needed to confirm these findings. Flow is a subjective state characterized by the following “intense and focused concentration on what one is doing in the present moment, merging of action and awareness, loss of reflective self-consciousness, a

sense that one can control one’s actions, distortion of temporal experience, and experience of the activity as intrinsically rewarding” [14]. - High levels of job support and workspace justice are protective for emotional exhaustion [19].

- For working mothers, work-to-family conflict is significantly related to burnout, whereas work-to-family enrichment is negatively related to burnout [11]. These findings suggest that a social support network could serve as a buffer for those dealing with an unhealthy working environment.

Burnout facts – treatment

- Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is effective in the reduction of burnout (64.64%) [21] and/or emotional exhaustion, a burnout subscale [20]. Mindfulness is also effective in the reduction of burnout symptoms (also 64.64%) [21].

- Stress management and music therapy are not better than CBT in the treatment of burnout [20].

- Spa treatment is effective in reducing burnout symptoms in people with mild or severe burnout up to 3 months after treatment [9], however, more research is needed to confirm these findings.

- More than half (55%) of the people on sick leave due to burnout used psychotropic prescription drugs, such as antidepressants and sleep medication [10].

Burnout facts – Literature

-

- [1] Embriaco, N., Azoulay, E., Barrau, K., Kentish, N., Pochard, F., Loundou, A., & Papazian, L. (2007). High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine, 175, 686-692.

- [2] Willcock, S., Daly, M., Tennant, C., & Allard, B. (2004). Burnout and psychiatric morbidity in new medical graduates.

- [3] Adriaenssens, J., De Gucht, V., & Maes, S. (2015). Determinants and prevalence of burnout in emergency nurses: A systematic review of 25 years of research. International journal of nursing studies, 52, 649-661.

- [4] Shirey, M., 2006. Stress and coping in nurse managers: two decades of research. Nurs. Econ. 24, 193–203.

- [5] Shimizutani, M., Odagiri, Y., Ohya, Y., Shimomitsu, T., Kristensen, T., Maruta, T., et al., 2008. Relationship of nurse burnout with personality characteristics and coping behaviors. Ind. Health 46, 326–335.

- [6] Grunfeld, E., Whelan, T. J., Zitzelsberger, L., Willan, A. R., Montesanto, B., & Evans, W. K. (2000). Cancer care workers in Ontario: prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 163, 166-169.

- [7] Ahola, K., Honkonen, T., Isometsä, E., Kalimo, R., Nykyri, E., Aromaa, A., & Lönnqvist, J. (2005). The relationship between job-related burnout and depressive disorders—results from the Finnish Health 2000 Study. Journal of affective disorders, 88, 55-62.

- [8] Vercambre, M. N., Brosselin, P., Gilbert, F., Nerrière, E., & Kovess-Masféty, V. (2009). Individual and contextual covariates of burnout: a cross-sectional nationwide study of French teachers. BMC Public Health, 9, 333.

- [9] Blasche, G., Leibetseder, V., & Marktl, W. (2010). Association of spa therapy with improvement of psychological symptoms of occupational burnout: a pilot study. Complementary Medicine Research, 17, 132-136.

- [10] Grensman, A., Acharya, B. D., Wändell, P., Nilsson, G., & Werner, S. (2016). Health-related quality of life in patients with Burnout on sick leave: descriptive and comparative results from a clinical study. International archives of occupational and environmental health, 89, 319-329.

- [11] Robinson, L. D., Magee, C., & Caputi, P. (2016). Burnout and the work-family interface: A two-wave study of sole and partnered working mothers. Career Development International, 21, 31-44.

- [12] Blom, V., Bergström, G., Hallsten, L., Bodin, L., & Svedberg, P. (2012). Genetic susceptibility to burnout in a Swedish twin cohort. European journal of epidemiology, 27, 225-231.

- [13] Mosing, M. A., Butkovic, A., & Ullen, F. (2018). Can flow experiences be protective of work-related depressive symptoms and burnout? A genetically informative approach. Journal of affective disorders, 226, 6-11.

- [14] Nakamura, J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., 2002. The concept of flow. In: Snyder, C.R., Lopez,

S.J. (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology. Oxford Univ Press, Oxford, pp. 89–105. - [15] Mather, L., Blom, V., & Svedberg, P. (2014). Stressful and traumatic life events are associated with burnout—A cross-sectional twin study. International journal of behavioral medicine, 21, 899-907.

- [16] Shin, H., Park, Y. M., Ying, J. Y., Kim, B., Noh, H., & Lee, S. M. (2014). Relationships between coping strategies and burnout symptoms: A meta-analytic approach. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45, 44.

- [17] Marchand, A., Juster, R. P., Durand, P., & Lupien, S. J. (2014). Burnout symptom sub-types and cortisol profiles: What’s burning most?. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 40, 27-36.

- [18] Linden, D. V. D., Keijsers, G. P., Eling, P., & Schaijk, R. V. (2005). Work stress and attentional difficulties: An initial study on burnout and cognitive failures. Work & Stress, 19, 23-36.

- [19] Aronsson, G., Theorell, T., Grape, T., Hammarström, A., Hogstedt, C., Marteinsdottir, I., … & Hall, C. (2017). A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and burnout symptoms. BMC public health, 17(1), 264.

- [20] Korczak, D., Wastian, M., & Schneider, M. (2012). Therapy of the burnout syndrome. GMS health technology assessment, 8.

- [21] Jaworska-Burzyńska, L., Kanaffa-Kilijańska, U., Przysiężna, E., & Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. (2016). The role of therapy in reducing the risk of job burnout–a systematic review of literature. Archives of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 4, 43-52.

- [22] INTeReSTS, D. O. (2015). Burnout in physicians. JR Coll Physicians Edinb, 45, 104-7.

- [23] Khattak, J. K., Khan, M. A., Haq, A. U., Arif, M., & Minhas, A. A. (2011). Occupational stress and burnout in Pakistans banking sector. African Journal of Business Management, 5, 810-817.

- [24] Leiter, M. P. (2005). Perception of risk: An organizational model of occupational risk, burnout, and physical symptoms. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 18, 131-144.

- [25] Schaufeli, W. B., & Maslach, C. (2017). Historical and conceptual development of burnout. In Professional burnout (pp. 1-16). Routledge.

- [26] Jamal, M. (2007). Burnout and self‐employment: a cross‐cultural empirical study. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress, 23, 249-256.

- [27] Wurm, W., Vogel, K., Holl, A., Ebner, C., Bayer, D., Mörkl, S., … & Hofmann, P. (2016). Depression-burnout overlap in physicians. PloS one, 11.

- [28] Middeldorp, C. M., Stubbe, J. H., Cath, D. C., & Boomsma, D. I. (2005). Familial clustering in burnout: a twin-family study. Psychological medicine, 35, 113-120.

- [29] Middeldorp, C. M., Cath, D. C., & Boomsma, D. I. (2006). A twin-family study of the association between employment, burnout and anxious depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 90, 163-169.

- [30] Wen, J., Cheng, Y., Hu, X., Yuan, P., Hao, T., & Shi, Y. (2016). Workload, burnout, and medical mistakes among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. Bioscience trends, 10, 27-33.