Coping with burnout – a self-help guide

Burnout is a huge problem for the individual suffering from burnout, but also for his/her family and productivity at work. Reducing burnout symptoms or preventing someone from developing burnout, therefore, is very important. The majority of the people with burnout are facing a high workload, low job control, long working hours, and work-to-family conflict, which makes it difficult for these individuals to reach out to a therapist/counselor for professional help. Fortunately, coping with burnout can be done alone and is not time consuming.

Someone who is effectively coping with burnout is able to set healthy boundaries, communicate in a transparent way at home and at work, values their own needs and desires, and is able to put things in perspective. This coping with burnout page focuses on the reduction of burnout symptoms using the most common causes of burnout.

At Barends Psychology Practice, treatment for burnout is offered. Go to contact us to schedule a first, free of charge, session. (Depending on your health insurance, treatment may be reimbursed).

Go to:

Coping with burnout – common causes

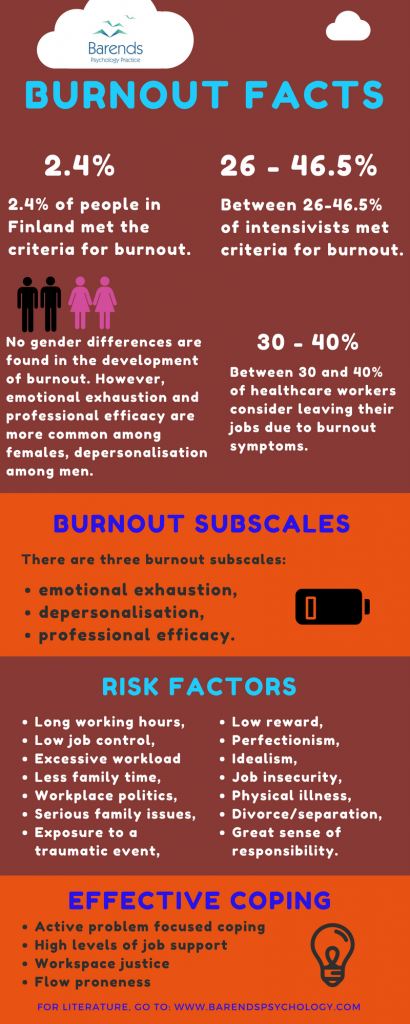

Burnout has three subscales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and reduced professional efficacy [1]. As mentioned on the main burnout page, an individual does not need to score high on all subscales in order to be burned out. There may be different causes that lead to a high score on emotional exhaustion and professional efficacy, compared to a high score on depersonalisation and professional efficacy. Here is a brief definition of the subscales and the common burnout causes:

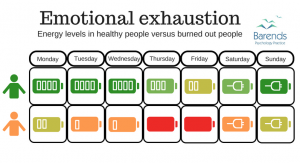

- Emotional exhaustion is characterized by a lack of energy and the inability to recharge energy levels. Feeling extremely tired, drained, and down are common in people who score high on this burnout scale [2].

- Depersonalisation is characterized by a distorted and impaired view of themselves, others, and one’s environment. As a results one may show a lack of empathy, loss of motivation, and a sense of isolation [2],[13],[14].

- Professional efficacy is characterized by concentration problems, difficulty focusing on tasks, and a negative attitude towards (work-related) tasks. Being listless and a lack of creativity is also common for people who score high on this subscale.

High scores on these subscales can be explained by a variety of reasons, and it’s most likely a combination rather than one single reason. Here are the main causes for people to develop burnout:

- Long working hours [3],

- High workload [3],[4],[5],[6],

- Low job control [7],[8],

- Organizational fairness [9],

- Work-to-family conflict [10],

- Having experienced traumatic events [11], and

- Supervisor’s leadership style [15],[16].

(Advertisement. For more burnout treatment information, continue reading).

Coping with burnout – what can you do to reduce burnout?

Coping with burnout is most effective when taking it one step at a time. A good way to reduce burnout symptoms is by taking away (or reducing the impact of) their causes:

-

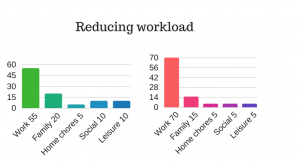

- Working hours: reducing working hours is associated with lower burnout rates [12]. Someone can work less or stick to their official working hours. Working less creates less stress and enables a person to recharge more in the mean time, as can be seen in the image. For some people, it is important to set healthy boundaries, to learn to say “no”, and to stick to the official working hours. Especially for sole traders, researchers, and managers sticking to a routine can be challenging. A routine helps someone to prepare for the end of a working day, gives them enough time to finish the last tasks, and lowers stress levels.

- High workload: a high workload increases the amount of professional mistakes one makes, stress levels, and extreme fatigue [10]. In some cases, the workload comes with the job (intensivists, crisis managers), but in other cases, the workload depends on the employee. Perfectionism, idealism, not being able to say no, a dependent personality, and fear of being rejected may all contribute to a high workload. There are a few things one can do to reduce the workload:

(1) slow down productivity – Take more short breaks, take more time to finish a certain task, or inform your coworker/supervisor only a few hours/day(s) after a certain task is finished. This will give a person time to recharge, and prevents a boss from demanding more.

(2) create a chart/diagram with activities and estimate how much energy it takes on a weekly basis. We’ve created an example (see image) where the person spends 70% of its energy on work and only has 5% left for leisure activities. 5% is too little to be able to recharge properly. By readjusting workload and working hours (no overtime, for instance) this person can spend more time with family, friends, and alone. This will reduce burnout in the long run. This diagram can also be made for tasks at work. This way it is easier to accept new tasks or to say no to requests.

(3) Dare to ask. Asking for help and assistance creates more time and less stress. A person is always free to ask for help and assistance and does not reflect negatively on the professional efficacy of a person. - Low job control: increasing job control reduces emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and improves professional efficacy [6],[7]. Being able to control various aspects of their job, such as when to do which task, when to take leave or a coffee break, increases the employee’s satisfaction significantly. Introducing a routine can improve this aspect tremendously, because a routine gives people a sense of control.

- Organizational fairness: this may be a hard one to change alone. If possible, schedule a meeting with your supervisor and ask for clear guidelines and regular feedback on job performance. The guidelines improve organizational fairness. The feedback reduces the emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and improves the professional efficacy [9]. Be careful with this one, because someone may lose their job if they try to change the organizational culture.

(Advertisement. For more burnout treatment information, continue reading).

- Work-to-family conflict: clear communication with your partner and not breaking promises will reduce the amount of work-to-family conflicts. By prioritizing family over work, it is easier to say no to work related requests. Also, keeping a partner updated about work, upcoming work related events, and deadlines, enables your partner to prepare for these days. Anticipation reduces stress, frustration, and conflicts. For more information about communication in relationships, click here.

- Having experienced traumatic events: always reach out to a professional who is specialized in trauma/PTSD treatment, because the effects of a traumatic event on daily life are always negative and may last for years if not treated. Coping with burnout is easier and more effective if PTSD is not affecting someone anymore.

- Leadership style: There are roughly four noteworthy leadership styles: transactional, laissez-faire, democratic, and transformational leadership style; the last two being the most effective ones [9]. These two leadership styles focus on the input of their employees and on encouragement, rewards, and on job control, which leads to more engagement.

Go to:

Coping with burnout – Literature

- [1] INTeReSTS, D. O. (2015). Burnout in physicians. JR Coll Physicians Edinb, 45, 104-7.

- [2] Gorter, R., Freeman, R., Hammen, S., Murtomaa, H., Blinkhorn, A., & Humphris G. (2008). Psychological stress and health in undergraduate dental students: fifth year outcomes compared with first year baseline results from five European dental schools. Eur J Dent Educ., 12, 61–68.

- [3] Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Vanroelen, C. (2014). Burnout among senior teachers: Investigating the role of workload and interpersonal relationships at work. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 99-109.

- [4] Greenglass, E. R., Burke, R. J., & Fiksenbaum, L. (2001). Workload and burnout in nurses. Journal of community & applied social psychology, 11, 211-215.

- [5] Wen, J., Cheng, Y., Hu, X., Yuan, P., Hao, T., & Shi, Y. (2016). Workload, burnout, and medical mistakes among physicians in China: A cross-sectional study. Bioscience trends, 10, 27-33.

- [6] Salanova, M., Peiró, J. M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2002). Self-efficacy specificity and burnout among information technology workers: An extension of the job demand-control model. European Journal of work and organizational psychology, 11, 1-25.

- [7] Lourel, M., Abdellaoui, S., Chevaleyre, S., Paltrier, M., & Gana, K. (2008). Relationships between psychological job demands, job control and burnout among firefighters. North American Journal of Psychology, 10, 489-496.

- [8] Hätinen, M., Kinnunen, U., Pekkonen, M., & Kalimo, R. (2007). Comparing two burnout interventions: Perceived job control mediates decreases in burnout. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 227.

- [9] Greco, P., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Wong, C. (2006). Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment and work engagement/burnout. Nursing Leadership, 41-56.

- [10] Wang, Y., Chang, Y., Fu, J., & Wang, L. (2012). Work-family conflict and burnout among Chinese female nurses: the mediating effect of psychological capital. BMC public health, 12, 915.

- [11] Katsavouni, F., Bebetsos, E., Malliou, P., & Beneka, A. (2015). The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries in firefighters. Occupational medicine, 66, 32-37.

- [12] Martini, S., Arfken, C. L., & Balon, R. (2006). Comparison of burnout among medical residents before and after the implementation of work hours limits. Academic Psychiatry, 30, 352-355.

- [13] Michal, M., Sann, U., Niebecker, M., Lazanowsky, C., Kernhof, K., Aurich, S., … & Berrios, G. E. (2004). Die Erfassung des Depersonalisations-Derealisations-Syndroms mit der Deutschen Version der Cambridge Depersonalisation Scale (CDS). PPmP-Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie, 54, 367-374.

- [14] Eckhardt-Henn, A. (2004). Dissoziative Störungen des Bewusstseins. Psychotherapeut, 49, 55-66.

- [15] Harms, P. D., Credé, M., Tynan, M., Leon, M., & Jeung, W. (2017). Leadership and stress: A meta-analytic review. The Leadership Quarterly, 28, 178-194.

- [16] Schyns, B., & Schilling, J. (2013). How bad are the effects of bad leaders? A meta-analysis of destructive leadership and its outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 138-158.