What is bipolar disorder?

What is bipolar disorder?

People with bipolar disorder experience significant mood swings, major fluctuations in energy levels, changes in activity, and difficulty carrying out daily tasks. These mood shifts can occur as frequently as several times a day or as infrequently as a few times per year. The severity and disruptive nature of bipolar symptoms often make it challenging to maintain healthy relationships or hold down a job for extended periods. Additionally, individuals with bipolar disorder are at higher risk of developing dementia [20], obesity, and metabolic syndrome [21]. They also have a significantly increased risk of suicide—most commonly during a depressive episode [17].

Fortunately, bipolar disorder is treatable. With the right counseling and treatment, the intensity of symptoms can be reduced, allowing individuals to lead healthy and fulfilling lives. This page covers the following topics: explanation of bipolar disorder, symptoms, risk factors, and important facts.

Quick Jump-to menu:

- Bipolar causes, treatment, and diagnosis.

- Bipolar disorder self-help and partner-help (coming soon).

- Bipolar disorder online test (coming soon).

- Online treatment for bipolar disorders.

- Back to the homepage.

At Barends Psychology Practice, we offer therapy for bipolar disorder. Schedule a first, free-of-charge session today. Go to: contact us.

Bipolar Disorder Terminology

Mania – This refers to an elevated or extremely energetic mood, known as mania or hypomania (depending on severity). During a manic episode, individuals often feel euphoric, full of energy, and sometimes irritable. They may act impulsively, take unnecessary risks, and sleep very little.

Depression – Depressive episodes are marked by feelings of sadness, anxiety, guilt, hopelessness, and isolation. People may lose interest in activities they usually enjoy, experience changes in appetite and sleep, and report feeling empty or emotionally numb.

Mixed affective episodes – In these episodes, symptoms of mania and depression occur simultaneously. This combination increases the risk of suicide, as impulsive behavior may be fueled by intense despair.

(Advertisement. For more information, continue reading.)

Bipolar Types: I, II, Cyclothymia, and NOS

There are four primary types of bipolar disorder: Type I, Type II, Cyclothymia, and Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (NOS).

Bipolar Type I is characterized by at least one full-blown manic episode lasting at least one week. The symptoms are severe enough to disrupt work, daily functioning, and social life. Hospitalization is sometimes required to prevent harm to oneself or others.

Bipolar Type IIis less severe than Type I. Although individuals experience hypomanic episodes, they are generally able to function in daily life. However, depressive episodes tend to be longer and more debilitating.

Cyclothymia is a milder form of bipolar disorder involving chronic fluctuations between short periods of hypomanic and depressive symptoms. These episodes are not severe enough to meet the criteria for Bipolar I, II, or Major Depressive Disorder.

Bipolar disorder Not Otherwise Specified is a diagnostic category used for bipolar symptoms that don’t clearly fit into the types above. This includes cases like drug-induced bipolar disorder or bipolar symptoms caused by a medical condition.

Bipolar Disorder Symptoms.

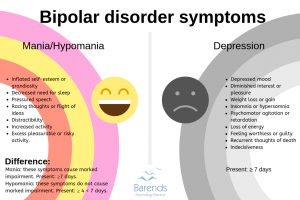

Bipolar symptoms are grouped into manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes. Because the symptoms in each episode can be quite contradictory—ranging from hyperactivity and euphoria to lethargy and despair—it’s helpful to understand them separately. For example, during a depressive episode, a person may feel exhausted, sleep excessively, and lose interest in daily activities. In contrast, a manic episode might be characterized by high energy, inflated self-esteem, and little need for sleep.

Bipolar symptoms are grouped into manic, hypomanic, and depressive episodes. Because the symptoms in each episode can be quite contradictory—ranging from hyperactivity and euphoria to lethargy and despair—it’s helpful to understand them separately. For example, during a depressive episode, a person may feel exhausted, sleep excessively, and lose interest in daily activities. In contrast, a manic episode might be characterized by high energy, inflated self-esteem, and little need for sleep.

Below is a breakdown of depressive episode symptoms:

- Symptoms must be present nearly every day,

- They must cause functional impairment, and

- They cannot be better explained by other mental disorders, substance use, or medication side effects.

Depressive Episode Symptoms:

- Persistent depressed mood most of the day,

- Significant weight loss or gain (not due to dieting),

- Loss of interest or pleasure in most activities,

- Insomnia or excessive sleeping (hypersomnia),

- Fatigue or loss of energy,

- Psychomotor agitation or slowing down,

- Difficulty concentrating or making decisions,

- Recurrent thoughts of death and/or suicidal ideation,

- Excessive or inappropriate guilt and feelings of worthlessness.

Manic episode:

There are three criteria to keep in mind when identifying a manic episode:

- The symptoms must be present nearly every day and for most of the day,

- The symptoms must last for at least one week (or require hospitalization), and

- The symptoms cannot be better explained by other mental disorders, substance misuse, or medication side effects.

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity,

- Pressured or rapid speech,

- Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feeling rested after only a few hours),

- Racing thoughts or flight of ideas,

- Easily distracted,

- Increased goal-directed activity (social, work, school, or sexual),

- Excessive involvement in pleasurable or risky activities (e.g., spending sprees, reckless driving, sexual indiscretions),

Hypomanic episode:

There are four criteria to keep in mind when identifying a hypomanic episode:- The symptoms must be present nearly every day and for most of the day,

- The symptoms must last between four and six days,

- The symptoms are not severe enough to cause marked functional impairment, and

- The symptoms cannot be better explained by other mental disorders, substance misuse, or medication side effects.

- Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity,

- Pressured or rapid speech,

- Decreased need for sleep,

- Racing thoughts or flight of ideas,

- Distractibility,

- Increased goal-directed activity or restlessness,

- Engagement in pleasurable but potentially harmful activities (e.g., impulsive purchases, risky behavior),

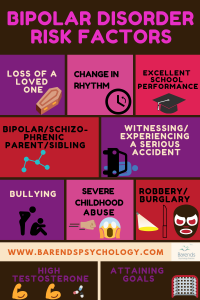

Bipolar Disorder Risk Factors

Several factors may contribute to the development of bipolar disorder or its symptoms. Importantly, having one or more risk factors does not mean someone will develop the disorder. A risk factor only indicates an increased likelihood.

Several factors may contribute to the development of bipolar disorder or its symptoms. Importantly, having one or more risk factors does not mean someone will develop the disorder. A risk factor only indicates an increased likelihood.

Genetics:

Having a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia significantly increases one’s risk [19]. The heritability of bipolar disorder is estimated at 59%, making genetics a strong contributing factor [19]. Interestingly, biological sex does not appear to influence the likelihood of developing bipolar disorder [19].

Stressful life events:

Experiencing significant stress or trauma can increase the risk of developing bipolar disorder [9]. These events may include:

- Losing a loved one,

- Moving to a new environment,

- Being robbed or involved in an accident,

- Being bullied.

Psychosocial:

Disruptions in social or circadian rhythms (your sleep–wake cycle) are also risk factors [9]. This emphasizes the importance of maintaining a regular daily routine and sleep schedule, especially for individuals with bipolar disorder. Negative social support—such as critical, guilt-inducing, or intrusive comments from close family or friends—can increase the risk of a bipolar episode and worsen symptoms [9]. Staying calm and supportive during someone’s manic or depressive episode can be incredibly challenging but is essential.

Cognitive/Academic Performance

Interestingly, research shows that individuals with excellent academic performance are four times more likely to develop bipolar disorder compared to average performers. On the other end of the spectrum, those with very poor school performance also have a moderately increased risk [22]. This suggests that extreme cognitive or emotional sensitivity may be a vulnerability factor.

(Advertisement. For more Bipolar disorder facts, continue reading).

Bipolar disorder facts

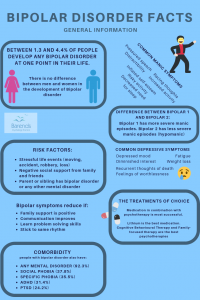

We’ve gathered interesting bipolar disorder facts from around the world and categorized them in different categories. Did you know that BD is not related to sex, family income or race/ethnicity [1],[6] or that people with BD have more bed-rest days due to emotional problems compared to people with other mental disorders [3]? Interestingly, one of the Bipolar disorder facts states that BD is responsible for more disability-adjusted life-years than cancer, epilepsy, and Alzheimer disease [5]. Another one of the Bipolar disorder facts is that one in four people with BP-1 or Any Bipolar Disorder report a history of suicide attempts compared to one in five with BP-2 [5],[7].

Bipolar disorder facts – Any bipolar disorder

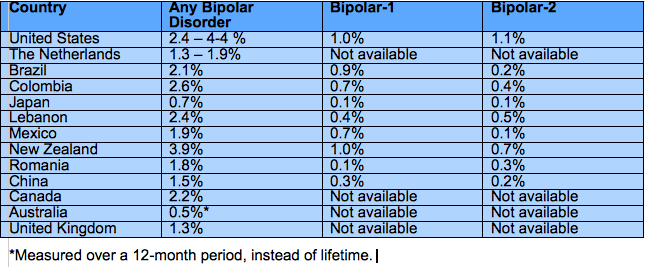

Between 0.7 and 4.4% of people experience any Bipolar disorder at one point in time [1],[2],[3],[4],[6],[8]. This includes: BD-1, BD-2, Cyclothymia, Substance-Induced BP, BP associated with another medical condition, and BD Not Otherwise Specified.

On average, in the United States, Bipolar disorders develop at the age of 20.8 years [1]. This is slightly later than the age of onset of Bipolar-1 and Bipolar-2. In Canada, however, the age of onset for Bipolar disorder is 22.5 years [6].

92.3% of the people with any Bipolar disorder meet the criteria for another mental disorder as well; for instance, one in every three people with Bipolar disorder also has social phobia (37.8%), ADHD (31.4%), one in every four people has PTSD, and one in every five people has Panic Disorder [1].

Bipolar disorder facts – Bipolar disorder 1

Between 0.4 and 1% of adults experiences Bipolar disorder 1 at one point in their life; 0.8% of men and 1.1% of women [1],[2]. Some countries report 0.1% of their population, but they used different criteria. Interestingly, some studies report no gender differences in people with bipolar disorder [19].

The age of onset for BP1 is 18.2 years: in retrospect people with BP-1 experienced either a manic/hypomanic or major depressive episode at 18.2 years [1].

People with BP-1 reported an average of 10.3 years in episode (manic/hypomanic/major depressive episode) [1].

Approximately one in three people (35.3%) with BP-1 received inappropriate medication in the past 12 months [1]. 46.8% received no medication at all [1].

97.7% of people with Bipolar-1 meets the criteria for another mental disorder as well; for instance, almost half of the people with Bipolar-1 also has social phobia (51.6%) or specific phobia (47.1%), one in every three people has Panic Disorder (29.1%), PTSD (30.9%), and one in every four people has OCD [1].

Bipolar disorder facts -Bipolar disorder 2

Between 0.1 and 1.1% of adults experiences Bipolar disorder 2 at one point in their life; 0.9% of men and 1.3% of women [1],[2]. Interestingly, some studies report no gender differences in people with bipolar disorder [19].

For Bipolar disorder 2, the age of onset is 20.3 years: in retrospect people with BP2 experienced either a manic/hypomanic or major depressive episode at 20.3 years [1].

On average, people with BP-2 are in episode for 11.6 years (manic/hypomanic/major depressive episode) [1].

One in four people (24.5%) with BP-2 received inappropriate medication in the past 12 months [1]. 59.9% received no medication at all [1].

95.8% of people with Bipolar-2 meets the criteria for another mental disorder as well; for instance, one in every two people with Bipolar-2 also has specific phobia (51.1%), social phobia (54.6%), one in three people has PTSD (34.3%), GAD (37.0%), one in four people has Panic Disorder (27.2%), and one in every five people has OCD (20.8%) [1].

Bipolar disorder facts – Risk factors

Prior to onset or subsequent episodes of Bipolar disorder, individuals often experience stressful life events [9]. A stressful life event increases the chance of developing a depressive episode as well as a manic/hypomanic episode. Stressful life events could be a renovation, moving to a different city/country, a serious accident, robbery, the loss of a significant other, and so on.

(Advertisement. For more Bipolar disorder facts, continue reading).

Research suggests that life events that disrupt the circadian rhythm or daily social rhythms more often predict mood episodes (depression, manic or hypomanic) compared to life events that do not disrupt the circadian or daily social rhythm [9]. During Ramadan, for instance, Muslims with BD more often experience an episode compared to the period outside Ramadan [9].

Goal striving or goal attainment is associated with experiencing manic/hypomanic episodes [9]. The theory behind these bipolar disorder facts is that people with BD respond with extreme positive effect, high energy, and motivation to events that involve high incentive motivations and goal striving. At the same time, people respond with extreme negative effect, anhedonia, and low energy to situations involving uncontrollable loss and failure [9].

Negative social support from family and friends predicts a worse course of bipolar disorder or the bipolar disorder symptoms. An example of negative social support: high expressed emotions [9].

Severe childhood abuse is a predictor of bipolar disorder later in life. Almost half of the people with bipolar disorder experienced severe childhood abuse [18]. People with bipolar disorder who were severely abused as a child also experienced their first episode earlier compared to those without a history of childhood abuse [18].

Positive social support from family and friends, on the other hand, can serve as a buffer against the deleterious effects of stress, and can enhance functioning among people with BD [9]. Positive social support can reduce the impact of some of the bipolar disorder symptoms

Problem solving skills, better communication, and psycho-education reduce the effects of BD and the chances of a relapse [9].

The chance of developing bipolar Disorder increases 13.63-fold when a sibling or parent has BD or another mental disorder [10].

Losing a mother before age 5 is also associated with increased chances (4.05-fold) of developing BD [10].

Research suggests that Bipolar disorder is a polygenic disease influenced by many genes that each contribute a little bit [11].

The suicide rate is 25 times higher for people with Bipolar disorder compared to the normal population [17]. Suicidal behaviour almost exclusively occurs during a depressive episode [17].

Higher testosterone levels are associated with more manic episodes and more suicide attempts [16].

Bipolar disorder facts – Treatment

Lithium has been the drug of choice for decades for the treatment of Bipolar disorder. Lithium is a mood stabilizer [12] and helps most of the bipolar disorder symptoms to reduce or disappear. Lithium and the anticonvulsant lamotrigine are the only two medications for which long-term efficacy has been established in at least two placebo-controlled studies [13].

During Lithium treatment the annual attempted suicide rate is 13-fold lower compared to the annual attempted suicide rate while not taking Lithium [13],[14].

Cognitive-behavioural therapy, family-focused therapy, interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, group psychoeducation, and systematic care management are all evidence-based treatments for Bipolar disorder [15].

Psychotherapy is most likely not effective during a manic episode, because of insufficient insight or rejection of help [15].

Bipolar disorder facts – Literature

[1] Merikangas, K. R., Akiskal, H. S., Angst, J., Greenberg, P. E., Hirschfeld, R. M., Petukhova, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2007). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of general psychiatry, 64, 543-552.

[2] Merikangas, K. R., Jin, R., He, J. P., Kessler, R. C., Lee, S., Sampson, N. A., … & Ladea, M. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of bipolar spectrum disorder in the world mental health survey initiative. Archives of general psychiatry, 68, 241-251.

[3] ten Have, M., Vollebergh, W., Bijl, R., & Nolen, W. A. (2002). Bipolar disorder in the general population in The Netherlands (prevalence, consequences and care utilisation): results from The Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Journal of affective disorders, 68, 203-213.

[4] de Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., van Gool, C., & van Dorsselaer, S. (2012). Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 47, 203-213.

[5] World Health Organization, The World Health Report 2002: Reducing Risks, Promoting Healthy Life. Geneva, Switzerland World Health Organization, 2002.

[6] Schaffer, A., Cairney, J., Cheung, A., Veldhuizen, S., & Levitt, A. (2006). Community survey of bipolar disorder in Canada: lifetime prevalence and illness characteristics. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 9-16.

[7] Mitchell, P. B., Slade, T., & Andrews, G. (2004). Twelve-month prevalence and disability of DSM-IV bipolar disorder in an Australian general population survey. Psychological Medicine, 34, 777-785.

[8] Smith, D. J., Nicholl, B. I., Cullen, B., Martin, D., Ul-Haq, Z., Evans, J., … & Hotopf, M. (2013). Prevalence and characteristics of probable major depression and bipolar disorder within UK biobank: cross-sectional study of 172,751 participants. PloS one, 8, e75362.

[9] Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., Urosevic, S., Walshaw, P. D., Nusslock, R., & Neeren, A. M. (2005). The psychosocial context of bipolar disorder: environmental, cognitive, and developmental risk factors. Clinical psychology review, 25, 1043-1075.

[10] Mortensen, P. B., Pedersen, C. B., Melbye, M., Mors, O., & Ewald, H. (2003). Individual and familial risk factors for bipolar affective disorders in Denmark. Archives of general psychiatry, 60, 1209-1215.

[11] Baum, A. E., Akula, N., Cabanero, M., Cardona, I., Corona, W., Klemens, B., … & Georgi, A. (2008). A genome-wide association study implicates diacylglycerol kinase eta (DGKH) and several other genes in the etiology of bipolar disorder. Molecular psychiatry, 13, 197.

[12] Su, Y., Ryder, J., Li, B., Wu, X., Fox, N., Solenberg, P., … & Ni, B. (2004). Lithium, a common drug for bipolar disorder treatment, regulates amyloid-β precursor protein processing. Biochemistry, 43, 6899-6908.

[13] Goodwin, F. K., Fireman, B., Simon, G. E., Hunkeler, E. M., Lee, J., & Revicki, D. (2003). Suicide risk in bipolar disorder during treatment with lithium and divalproex. Jama, 290(11), 1467-1473.

[14] Baldessarini, R. J., Tondo, L., & Hennen, J. (2001). Treating the suicidal patient with bipolar disorder. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 932, 24-43.

[15] Geddes, J. R., & Miklowitz, D. J. (2013). Treatment of bipolar disorder. The Lancet, 381, 1672-1682.

[16] Sher, L., Grunebaum, M. F., Sullivan, G. M., Burke, A. K., Cooper, T. B., Mann, J. J., & Oquendo, M. A. (2012). Testosterone levels in suicide attempters with bipolar disorder. Journal of psychiatric research, 46, 1267-1271.

[17] Rihmer, Z. (2009). Suicide and bipolar disorder. In Bipolar depression: molecular neurobiology, clinical diagnosis and pharmacotherapy (pp. 47-56). Birkhäuser Basel.

[18] Garno, J. L., Goldberg, J. F., Ramirez, P. M., & Ritzler, B. A. (2005). Impact of childhood abuse on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 186(2), 121-125.

[19] Lichtenstein, P., Yip, B. H., Björk, C., Pawitan, Y., Cannon, T. D., Sullivan, P. F., & Hultman, C. M. (2009). Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. The Lancet, 373, 234-239.

[20] Kessing, L. V., & Andersen, P. K. (2004). Does the risk of developing dementia increase with the number of episodes in patients with depressive disorder and in patients with bipolar disorder?. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 75, 1662-1666.

[21] Fiedorowicz, J. G., Palagummi, N. M., Forman-Hoffman, V. L., Miller, D. D., & Haynes, W. G. (2008). Elevated prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 20, 131-137.

[22] MacCabe, J. H., Lambe, M. P., Cnattingius, S., Sham, P. C., David, A. S., Reichenberg, A., … & Hultman, C. M. (2010). Excellent school performance at age 16 and risk of adult bipolar disorder: national cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196, 109-115.